|

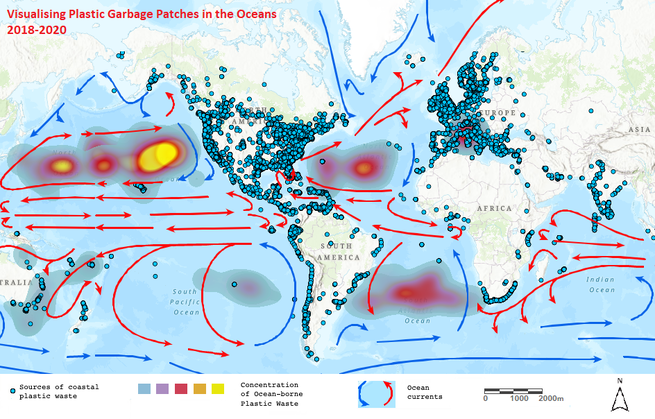

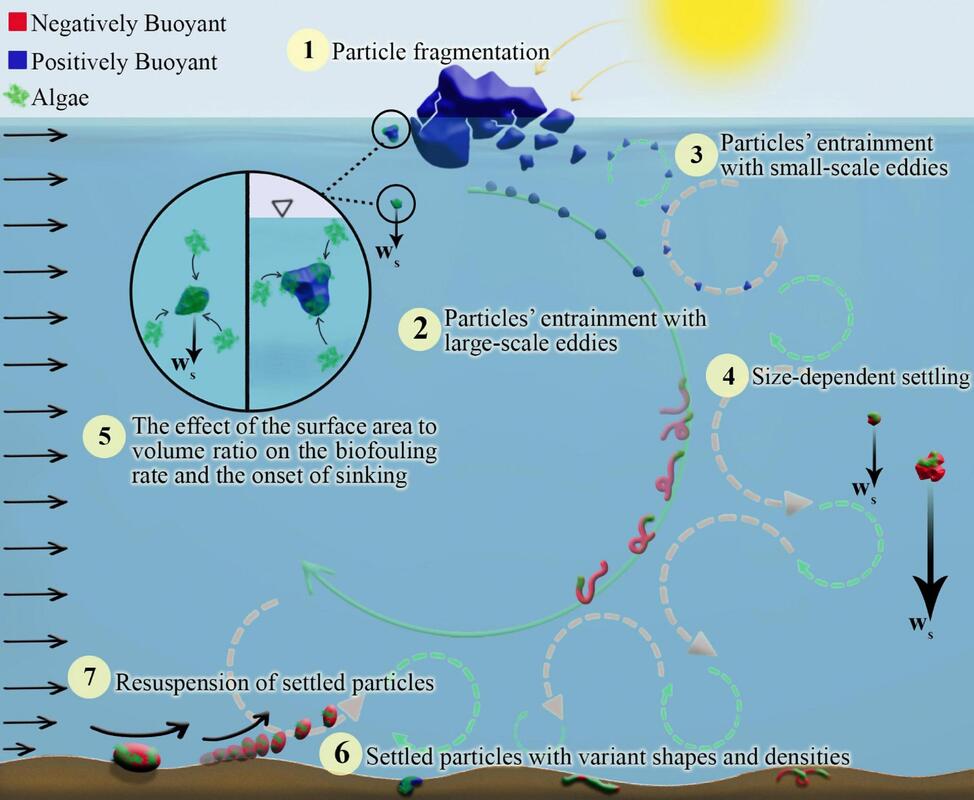

What happens when a tree dies close to a river, or to the sea shore? Easy: wood floats so currents take it with them, together with its inhabitants. Once it’s in the water more creatures take advantage of this drifting island full of organic nutrients, floating debris are in fact one of the mechanisms that allow species to expand geographically. Of course trees decompose, and the expansion of the species that depend on them unavoidably happens according to the decay timeline of their rafts. But what happens when rafts never decay? Since the 1950s we have discarded tons and tons of a material that’s mostly lighter than water, a lot of which eventually ends up in the seas: plastic. And we are not slowing down, on the contrary. Half a century later we realized that all that plastic that ended up in the oceans, would concentrate in areas where it was corralled by currents. In 1997 the “Pacific Garbage Patch” was finally discovered, and it was only the first one. Plastic waste is collected within all gyres, the areas around which ocean currents rotate, and gyres are everywhere. Now we know of the “North Atlantic Garbage Patch”, the “South Atlantic Garbage Patch”, the “North Pacific Garbage Patch”, the “South Pacific Garbage Patch” (yes, there are two mayor “Patches” in the Pacific Ocean), and the Indian Ocean Garbage Patch”. These are only the mayor ones, the ones that were large enough for us to name. But plastic concentrates in all gyres, large and small. Basically, and even if they are way less visible than large landfills, our waters are chock-full of plastic. But mind you, they rarely look like this. Plastic in our seas mostly looks like a soup of suspended particles that range in size from metronomes to a few centimeters, with larger chunks interspersed on the surface, at the bottom and even floating in the middle. The larger blobs are death traps for many marine creatures that get entangled in them, while the smaller particles are eaten and have become, with time, unavoidable component of our own lives: they are, in fact, inside each and every one of us, as well as all other living creatures. We, as the land-faring species we are, often forget that creatures who dwell in water (and air) live in three dimensions. We are limited by gravity and move only back and forth, left and right, while marine animals move also up and down. So does plastic in water. On land plastic, pinned down by gravity, can “only” cover surfaces, however in the liquid medium it fans out in 3D. This means that the concentration of plastic in the sea is way lower than on land, but spread way deeper. So, this is what we already knew. After discovering the first “Great Garbage Patch” in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, a place that was supposed to be pristine for its sheer enormity and distance from any human settlement, many have tried to clean it up. This effort, until now, was considered to be a good thing. Although if there’s anything we know about life, is that it’s stubborn. Life attaches itself to deep oceanic vents, to sulfuric lakes, it can even exist in space under certain conditions. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that it would also attach itself to even the smallest floating raft in the middle of an ocean. And it has. Life exists without our permission. After almost a century of floating plastic rafts, it has taken advantage of them and has created new ecosystems. Our plastic garbage has become the home of billions of individuals, who depend on them for their survival. And this is what we are finding out now. So now we are faced with a conundrum. After having literally trashed the existing marine ecosystems, life has adapted and created new ones on humankind waste. And we want to take THAT away too? Soupy islands of floating plastic debris where species are taking shelter, growing, reproducing, evolving. Whole new ecosystems. Think about that. Now, wouldn’t cleaning out the garbage patches lead to the destruction of an existing ecosystem, as much as clearing out a patch of forest would? Admittedly, the ecosystem of a patch of forest might be older, but does it matter? There are definitely creatures large and small living within plastic patches in the oceans, why should it matter that they have “only” been there for a century? How many generations is that for a sea slug or a mussel anyway? Is it right to kill them by forcibly taking them out of their habitat and destroying it altogether? Shouldn't we keep in mind that it’s exactly these species that constitute the basis structure of the global food chain, and that on top of it all they are otherwise being wiped out all over the globe? On the other hand, would leaving the plastic patches as they are be untenably harmful to the rest of the existing, more established marine ecosystems? Are we doing it wrong? Are there other ways to safeguard the creatures for which plastic is detrimental, while at the same time protecting the new communities that are evolving with and on it? Right now only one thing is certain: we have been disrupting each and every ecosystem on a global scale for a very long time. We won’t find an easy solution to this, nor any of the issues that we are and will be facing. At this point, most options will probably be more “patch-ups” than “fixes”, as the perfect solution might not even exist. And since we continue disrupting, reality will get more and more complex, so we might want to think about that too. To patch-up the issue at hand, some people are advocating for collecting plastics before it gets to the seas by placing specific filters at the mouths of rivers. But even if we somehow did get to install and maintain them, filters have evident drawbacks as many animals need to go in and out of rivers, and a good percentage of plastic particles might even be too small to be stopped by filters anyway. Also, not all plastic pours into the ocean from rivers. Other people push for hand-collecting plastic debris while creating alternative habitats that would replace the existing ones, although we all realize how enormous this endeavor would be. Of course limiting plastic use would take care of the issue from its root, but if we are really honest with ourselves, we all know that plastic is going to stay with us for a very, very long time. The mere fact that you are reading this means you are using plastic, in your phone, in your computer or tablet. On the other hand we should also admit that we don’t really NEED to use plastic as much as we do. One thing is to use it for a syringe or a hospital drip, another is to use it in and around our food, clothes, and the thousand of items that, if we continue being honest, aren’t really necessary. Communication is a basic human right. A play station or the newest mobile phone model still aren’t. Maybe let’s start thinking about curbing our consumption, our plastic use will automatically decrease. This is something we can all do, on our own, without having to wait for any government or organization to do it for us. I don’t have answers to the questions above, and the many more that arise from this situation. I don’t think anybody has, if we really consider the complexity of it all. But this is something WE created, for good or for bad. We created it by ignorance, disinterest, complacency, arrogance, overconfidence, egoism and a good sense of superiority. Maybe changing all that should be the first step. The solution, if there is one (probably only a “patch-up” but better than nothing at all) unavoidably goes through being aware of the deep and long-lasting consequences of our choices. Something else we might want to change is the consideration of our place within nature. We think we “rule” the world, instead we are merely a passenger. We think we can “dominate” the natural world, instead we are just slightly changing it, just enough to start worrying about our survival. We are astonished each time we see nature running its course, not caring for humans at all, taking what it’s given and adapting. Nature doesn’t need to wait for us to “discover”, to “worry”, to “repair”. It does it all by itself, forever oblivious to our worries and delusions of grandeur. The mere attempt of clean up the oceans of plastic comes from hubris, from thinking that we can fix something we’ve broken. On the other hand we might decide to let nature take its course, as we have until now. I think recognizing that we must do whatever we can, admitting at the same time how little we will be able to achieve, is indispensable to face the destruction of the only ecosystem that allows our lives. With all we have, we should find ways for fixing what we still can, humbly understanding that we are only a tiny (though unrelenting) member of the global ecosystem, and fully assuming the responsibility of being the cause of so many changes. It might be a good time to realize how small we are, and at the same time take responsibility of the havoc we have been wreaking since the dawn of the industrial revolution. We are not “destroying the world”, we are merely changing the conditions within which we -and many other species, albeit not all- are able to survive. After we are gone, life will still be here. Maybe even floating on plastic debris in the middle of the post-antropocene oceans.

|

The AuthorA Mind full of Ideas Archives

June 2018

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed